Today, we stand at a similar turning point. We are again called to reconsider our pathways, to reflect on the systems we have built, and to innovate boldly so that these systems can be transformed. Only then – by recognising ourselves as an integral part of larger environmental systems – can we steer toward more sustainable, safer, and more resilient futures.

We encourage everyone engaged in futures thinking or involved in decision-making – across sectors and levels – to explore the report and its findings. GEO-7 offers a clear and comprehensive overview of current trends and shows that, although today’s policies are driven by good intentions and represent the best that governments, businesses, and communities are currently able to do, they are still not enough. Yet this is not a moment for pessimism, paralysis, or retreat from green ambitions.

We are again called to reconsider our pathways, to reflect on the systems we have built, and to innovate boldly so that these systems can be transformed. Only then – by recognising ourselves as an integral part of larger environmental systems – can we steer toward more sustainable, safer, and more resilient futures.

In today’s world, environmental crises are deeply intertwined with other crises. The war in Ukraine, for example, has devastating consequences for geopolitical security, while at the same time delivering a profound shock to natural systems – one that further intensifies existing environmental pressures. These overlapping crises remind us that there is no such thing as lasting economic prosperity under mounting environmental stress. When climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution accelerate, they erode not only ecosystems but also social cohesion, especially in the most vulnerable places, thereby compounding insecurity and instability across societies.

What is there to transform?

Achieving international environmental goals generates powerful cascading benefits for human security, public health, and the overall well-being of societies. In other words, acting decisively on environmental commitments is not only about protecting the planet – it is about safeguarding people and strengthening the foundations of thriving nations.

GEO-7 calls for accelerated transformations and provides a clear methodology for assessing available solution spaces.

Transformation goes beyond change or transition. Change adjusts parts of a system, and transition moves us from one state to another. Transformation, however, reshapes the system itself. And in case of the 7th Global Environmental Outlook, several key systems need to be reshaped: the economic and financial system, material and waste system (circularity), energy system, and food system.

One of the most distinctive features of this report is its effort to bring together technology-oriented and behaviour-oriented solutions. Policy prescriptions are plentiful in many analyses and reports. However, GEO-7 speaks directly to how transformations can actually be achieved. And, of course, there are no simple answers.

The report examines in detail the levers, broadly understood as areas of intentional action, that help us understand how to enable the transformations. These include economic and financial levers, individual and collective action lever, knowledge and innovation, governance, and capabilities levers.

Such a precise articulation of the levers, combined with their broad scope, truly allows decision-makers and change-makers across sectors to identify the solution spaces most relevant to their work. Whether you are an NGO leader, a member of a corporate board, a parliamentarian, or a city mayor, GEO-7 becomes an accessible tool for locating actionable and effective solution spaces within your own domain.

Role of social sciences and humanities

An important and often overlooked point is that we cannot rely on systems transformation without simultaneously addressing social norms, culturally grounded habits, and the social systems that shape governance and economic structures. Most importantly, we must consider the behaviour of individuals and large groups. For transformations to take root, shifts in other systems must occur alongside changes in individual lifestyles and household decisions.

For example, the slow adoption of renewables in the 1990s, despite significant technological advancements of those days, reflected the fact that societies were not yet prepared to shift their habits, norms, and expectations around energy use.

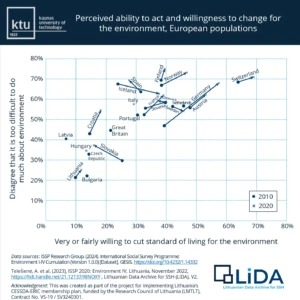

In this sense, it is particularly interesting to examine how people across European countries think about making more substantial adjustments to their own behaviour for environmental sustainability and circularity, and whether they are prepared to sacrifice aspects of their standard of living for the sake of the environment.

The potential for behavioural transformations across different societies depends on a wide range of psychosocial, structural, and contextual factors. It is important not to oversimplify by assuming that behaviour can be transformed through one or two incentives alone. To understand the current levels of societal readiness and willingness to act, we need a synthesis of social science knowledge and data – something that is still greatly lacking. This is an essential direction for further social research.

Societies are different with respect to behavioural transformation

There is, however, some interesting available survey data. Without claiming to provide a comprehensive assessment, we include here a short overview of cumulative International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) Environment data from the 2010 and 2020–2023 surveys for European countries. These data illustrate how willing different populations are to cut their standard of living for the environment, and how they perceive their own ability to act. The chart shows the percentage of respondents who strongly or somewhat disagree that “it is too difficult to do much about the environment” (Y-axis), meaning they have a higher sense of environmental efficacy. The X-axis shows the share of people who report being very or fairly willing to cut their standard of living for the environment. Full datasets can be accessed through the GESIS data archive or other social science data infrastructures within CESSDA-ERIC, including LiDA in Lithuania.