“Sustainability takes much more than simple problem-solving or some improvements in the existing consumption and production system. It requires a leap from the existing level of actions”, says Jurgis Kazimieras Staniškis, transdisciplinary scientist globally recognised for his innovative and transformative systems, Professor, Senior Researcher at Kaunas University of Technology (KTU) in the interview for COPERNICUS Alliance published below.

Ingrid Mulà (IM): Kaunas University of Technology joined the COPERNICUS Alliance in 2019. We are delighted to have your university in the network. In your view, what is the role of universities in society today and how can the COPERNICUS Alliance support this role?

Jurgis Staniškis (JS): Higher education around the world, especially nowadays, is subject to endless discussions and substantial reforms of performance management. A major catalyst of the currently very popular “third mission” and rethinking of the university’s role in technology transfer was the emergence of an independent relationship between science, industrial innovation and government policy leading to a so-called “knowledge-based” economy. At the same time, there are many good examples where co-creative partnerships for sustainability are implemented in a way that is fundamentally different from conventional third mission activities.

In this context, the COPERNICUS Alliance could be a good platform for the development of, and sharing of experience with, co-creation processes for sustainability, addressing local sustainability issues by generating socio-technical and environmental transformations with the goal of materializing sustainable development in a given geographical vicinity.

Sustainability learning challenges require new ways of producing transdisciplinary knowledge with the involvement of actors from outside academia in order to meet the goals of sustainability science as a community-based transformational scientific field. The traditional model of the university, based on the pre-eminence of single-discipline departments, should be stretched and challenged because there is clear evidence that department-based structures are essentially at odds with transdisciplinary collaboration and thus with learning for sustainable development. The university of the future should include a broad range of community members and actively engage in issues that concern them; it should also be relatively open to commercial influence and fundamentally transdisciplinary in its approach to both teaching and research.

IM: You certainly have a long experience of leading transdisciplinary co-creation processes with the community, and especially of working with industry. You developed an interesting system for supporting the generation of sustainable innovations, financing and implementation, in which an international bank was involved. Can you briefly describe this system and tell us how it enables those innovations to achieve sustainability in companies?

JS: That is true. Sustainability takes much more than simple problem-solving or some improvements in the existing consumption and production system. It requires a discontinuous leap from the existing level of actions, leading to transformations where the reality changes its form. Even though reducing unsustainability is not the same as creating sustainability, it still makes great sense to prevent and remove the causes and sources of unsustainability; however, it is recognised that this is just attacking the symptoms. In this context, in my research, reducing unsustainable patterns is considered as a process of continuous improvement of environmental, economic and social performance in industry and other organisations by generating incremental preventive changes.

To reduce unsustainability in industry and other organisations, we developed a system for incremental generation, financing and implementation of innovations. Together with the international bank, we created a revolving financial facility that provides companies and organizations with soft loans for preventive innovations (innovations that focus on prevention of waste or overuse) with comparatively short payback implementation. The financial facility comprises a pool of so-called business development service providers for preventive innovation generation, financial engineering, implementation and monitoring, the financing source – soft credit line and companies or organizations. Innovations are identified and assessed with a methodology based on the company’s material and energy flows, and environmental and social costs are properly evaluated by using environmental management accounting. The methodology is flexible and can be applied to different types and levels of companies to provide decision-makers with information about their intended economic, environmental and social purposes.

The analysis of system implementation data clearly showed that the application of incremental preventive innovations to processes, products and services significantly increases production efficiency through optimisation of natural resource consumption (materials, energy, water) at different stages of production, minimises the generation of waste and emissions, and fosters safe and responsible production which leads to economic, reputational, and regulatory benefits. In total, from 1994 to 2014, 177 innovations were implemented in Lithuania, with investments exceeding EUR 23 million and confirmed annual savings of over EUR 13 million. The technical, economic and environmental assessments of preventive innovations were entered into a special database that allows fora comprehensive analysis of their efficacy and widescale distribution in various industrial sectors.

IM: This work is impressive and it really demonstrates that investing in sustainability matters a lot, creating clear benefits for companies and society as a whole. You are a professor at Kaunas University of Technology. Have you managed to transfer the new approach to innovations and knowledge to the university curriculum?

JS: There were several achievements, but the greatest is the development of the international master training programme “Cleaner Production and Environmental Management”. By integrating own research, experimental development and studies, and active participation of the BALTECH consortium of technical universities of the Baltic States, this programme was successfully launched at the Kaunas University of Technology in 2002 and later at other Baltic technical universities.

The main guiding principles for the structure of the programme are as follows: a transdisciplinary approach to sustainability, implemented through a strongly research-connected programme that integrates practical experience. Among the advantages of the programme are the class debates and the development of new ideas that originate from the multi-focus views enriched by real data from case studies.

The programme offers an integrated approach of current, long-term and strategic environmental issues, focusing on technologies and concepts in environmental planning and management for sustainable development of industrial production. Taking into account the different background of the students, the programme enables graduates to:

The programme has been awarded a Sustainability Certificate by the National ENERGY GLOBE’12 Award and was evaluated very positively by the European QUESTE-SI accreditation “Engineering education – for sustainable industries”.

IM: Your expertise in sustainable development is unquestionable. A few years ago you were selected by UN General Secretary Ban Ki-moon to be a member of the Independent Group of Scientists who compiled the Global Sustainable Development Report (GSDR)1. What insights from your experience in sustainable industrial development did you succeed in contributing during this process, and what did you learn?

JS: At the 2016 High-Level Political Forum, the United Member States took the decision to organise an independent group of scientists comprising 15 of the most known sustainable development science experts from various regions of the planet. At the end of 2016, after a careful selection procedure, UN General Secretary Ban Ki-moon personally appointed the scientists to prepare a Global Sustainable Development Report on fundamental transformations needed to reach the sustainable future outlined in the 2030 Agenda.

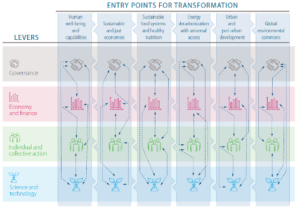

The Global Sustainable Development Report, entitled The Future is Now: Science for Achieving Sustainable Development was presented and positively approved by the UN High-Level Political Forum in July 2019 and by the UN General Assembly in September 2019. The report uses the latest scientific assessments, including personal investigations, evidence bases about good practices, and scenarios that link future trajectories to current actions, to identify new urgent calls to action by a range of stakeholders – including scientists – that can accelerate progress towards achieving sustainable development. A model of transformations for country or region-specific generation of pathways was elaborated. The model recognises that while the present state of imbalance across the three dimensions of sustainable development arises from not having fully appreciated the interlinkages across them, or having unduly prioritized the short term, it is those same interlinkages that will lead to the desired transformative change when properly taken into account. This basic understanding has guided our investigation’s concept and structure, leading to the identification of knowledge-based transformations for achieving sustainable development. Accordingly, six entry points were identified that offer the most promise for achieving a rebalancing at the scale and speed needed for the 2030 Agenda (Figure 1):

These entry points are the means to harness important synergies and multiplier effects and deal with trade-offs across the Sustainable Development Goals to accelerate progress. Countries and subnational entities could then develop acceleration roadmaps and pathways based on the scientific evidence most relevant to their circumstances and context.

However, the entry points alone are not sufficient for the transformations system, especially if actions do not adequately address global interconnections or take full account of the non-economic, but the intrinsic value of nature. Accordingly, four levers have been identified (Figure 1):

Each lever is a powerful agent of change in its own right and impacts the goals through the identified entry points. But true transformation is possible only when the levers are deployed together in an integrated and intentional manner. Transformations differ from an evolutionary or chaotic change in that they are intentional changes based on societal agreement and factual understanding, and achieve outcomes at different scales.

The model and system of transformations developed by the authors and presented in the GSDR clearly show how science-based evidence can illuminate sustainable paths enabling future generations to live within the limits of the Earth ecosystem. The need for such paths is critical and action must be bold and decisive, not just for a change but for systemic transformations.

The Report clearly demonstrates that sustainability science can help to tackle the trade-offs and contested issues involved in achieving sustainable development. The authors provided a successful interdisciplinary research process showing that individual researchers and research initiatives in different fields should become part of larger collective research projects and holistic programmes. Only long-term research partnerships can identify socially relevant questions, generate meaningful insights, and bridge the gap between knowledge and action. Simultaneously, to realize the sustainability science potential there need to be significant adjustments within universities and other research and training institutions.

IM: From what you are explaining, I cannot imagine the model working and the systems being transformed without actors being involved in truly transformative learning processes. Many of these actors might come from the higher education sector and will be university educated; but will they have the necessary competences to support sustainability transformation processes? In your view, what needs to be changed in university teaching to prepare our students and researchers for this future responsibility?

JS: First of all, the world today needs more sustainability science and an engaged academic community that sheds light on complex, often contentious and value-laden, nature-society interactions, with a view to generating usable scientific knowledge for sustainable development. This requires new priorities within the research communities, for example, expanding research agendas and capacity building, as well as broadening transformation of science as an institution. Educational institutions at every level, especially universities, should develop special transdisciplinary MSc and PhD study programs and incorporate high-quality courses of study on sustainable development with a sound theoretical basis and thorough orientation towards practice. The current science–policy environment frequently discourages that kind of research and studies and when considering proposals for funding, reviewers often apply specialized disciplinary criteria rather than taking into account the integrated whole. Thus, research institutions such as universities, academic and scientific associations and policymakers should expand their evaluation systems to recognize and prioritize interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary skills and reward research that strives for societal relevance and impacts. This obviously requires structural transformations towards sustainability at universities, as already mentioned earlier.

Finally, new initiatives are needed that bring together science communities, policymakers, funders, local representatives, and actors with practical and indigenous knowledge with other stakeholders to scale up sustainability science and transform scientific institutions towards engaged knowledge production for sustainable development.

IM: Thank you for all these insights. I totally agree that evaluation systems need to be challenged and a COPERNICUS Alliance Working Group is currently working on this, with the participation of a colleague of yours, Eglė Staniškienė. The last question: May we know about your future plans? Are you working on any specific personal or professional project?

JS: Currently, I am a manager and leading expert of a research project entitled “The Contradictions and Tensions of Organizations in Sustainability Transitions” (funded by the Research Council of Lithuania until the end of 2020). On the 1st of July, I started my activities at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Lithuania as an expert for the implementation of the SDGs in Lithuania and partner countries. Besides that, I am working on a book entitled “Transformation of an organization towards sustainability”, which should be published next year.

IM: Thank you very much for a very inspiring conversation. Please do inform us when the book is published so that we can share it with our network. It has been a pleasure to talk to you and we hope that we can continue collaborating through the COPERNICUS Alliance.

______

1 United Nations. 2019. The Future is Now: Science for Achieving Sustainable Development (Global Sustainable Development Report 2019). New York, United States: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs.https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/24797GSDR_report_2019.pdf